By Elizabeth Zach, RCAC staff writer

Moab, Utah –Emily Niehaus happily acknowledges she took a circuitous route to become a housing advocate. She tallies her master’s degree in applied sociology and following that, stints as a loan officer, bookkeeper and case worker.

“But those three jobs really pointed me in the direction of affordable housing,” says the founder and director of Community Rebuilds. “I see it as the solution that might solve different issues. Affordable housing solves everything from homelessness to depression.

“When I was working as a case worker in Moab,” continues the Ohio native, “I was seeing two or three families living together in these trailers. I also saw families losing custody of children because they didn’t have housing. That’s when I said, ‘I’m looking to build the cheapest house on the block.’”

And she’s made good on that promise, from foundation to finish.

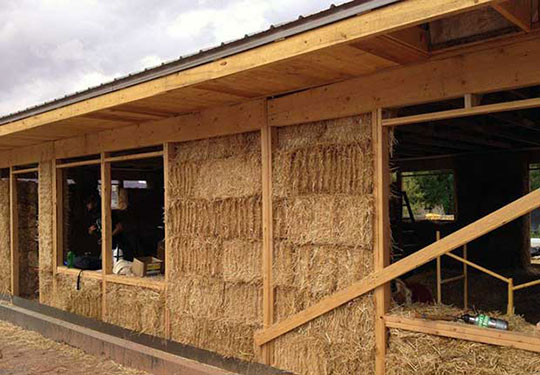

Since 2010, Community Rebuilds, in Moab, Utah, has helped prospective homeowners build their own energy-efficient, sustainable, affordable straw bale homes in Moab and Crested Butte. As with all self-help projects, production labor costs are minimal because Niehaus and her colleagues also train young volunteer interns to build these low-carbon, modern natural buildings that are easily replicable.

Niehaus is quick to credit Rural Community Assistance Corporation (RCAC) for its strong support, particularly in getting the program off the ground. RCAC regional manager, Carol Cohen, also recalls the early challenges.

“Because it was so out-of-the-box to use straw bale in a self-help program, we constantly ran up against a wall in terms of federal guidelines,” Cohen says. She explains that while prospective self-help homeowners often contribute the sweat equity to build their future homes, Community Rebuilds uses interns to do the bulk of the building, providing says Cohen, “a great economic development model. It’s a slight variation on the concept of sweat equity, but it works.”

“I realized that you can train young people to build, expanding on the self-help model,” Niehaus says. Community Rebuilds is the only organization anywhere that offers this free training to interns, including hands-on learning, free housing and a food stipend in trade. As of 2016, Community Rebuilds has trained 180 interns.

Cohen further explains that the program trains interns (students) to become sustainable builders. A few of Community Rebuilds’ emerging professionals have opened their own businesses in straw bale construction and permaculture landscaping. In addition, Community Rebuilds sources a larger percentage of their building materials locally and regionally with clay harvested locally and straw from farmers in Fruita, Colo., 100 miles away. The traditional construction products like lumber and nails purchased locally support businesses in town and the economic impacts ripple through the community. In short, straw bale housing is an alternative to existing typology for affordable housing construction.

As Niehaus says, “Community Rebuilds is a mechanism to change not only what is built but also how it is built,” and she adds that at first, building the straw bale homes was expensive, not because of the materials but because no one knew how to build them.

As Niehaus says, “Community Rebuilds is a mechanism to change not only what is built but also how it is built,” and she adds that at first, building the straw bale homes was expensive, not because of the materials but because no one knew how to build them.

The materials they use are appropriately called “dirt cheap”—mud, straw, clay, wood, recycled, salvaged and donated. The Moab homes cost around $70 per square foot, half the standard costs of construction in Moab’s tourism-based economy, where housing and land costs are high. All structures include solar energy infrastructure.

Moab’s affordable housing need is great but not obvious to all—including to Niehaus when she began this work. Moab draws many tourists to its two nearby national parks (Arches and Canyonlands) and numerous outdoor adventures. In the past several years, the population has morphed into a sizeable group of “amenities” residents with higher incomes, which has driven up the cost of living.

“In general,” Niehaus says, “we have sympathy toward the seasonal workers. But what about, say, the bike mechanics, or river guides? I’ve heard people say, ‘Well, at least their job is fun.’ But they still struggle to afford housing, to thrive and be anchored in their communities, have families, participate in the economy beyond employment. So, I wanted to find a housing solution for all service-industry workers, including the guides and mechanics.”

To date, Community Rebuilds has constructed 22 straw bale homes.

The hard work has not gone unnoticed. In December, the White House recognized Niehaus and her work with a Champions of Change Award. Instituted during President Obama’s administration, the award honors ordinary people doing extraordinary things in their communities. For Niehaus, the award is particularly momentous because her work, she says, really started in 2008 when Obama was elected president. His community organizing work and his approach to politics inspired her.

“I understood his message (“Yes We Can”) to be a partnership request,” she says, noting that she was pregnant with her son Oscar James at the time. “I had a role to play. And so I founded Community Rebuilds to address an affordable housing need in my rural community with the larger goal of shifting the existing construction paradigm to have a lighter impact.”

All along, the idea has been clear and simple—use volunteers to offset construction costs; offer low interest rates and affordable repayment plans using federal financing; and build with sustainable materials.

Her timing was good, too. As she sought financing to build the homes in 2009, she reached out to former RCAC rural development specialist, Dave Conine, who had recently been appointed U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development Utah state director. He connected her to the 502 Direct Loan Program, which helps low-income families purchase homes in rural communities, and the Rural Business Enterprise Grant, which paid for technical assistance and an instructor to teach alternative home construction.

“It’s because of Dave that I got the award,” Niehaus says. “He nominated me for it.”

At the time, recalls Conine, Niehaus had an idea to develop a trailer replacement housing program. He says he was immediately impressed with her commitment to helping people get into better housing. She later approached Rural Development about the straw bale housing.

“There was a lot of uncertainty as to whether we could do straw bale housing in rural development,” Conine says. “The question eventually came to my desk. I already knew Rural Development funded these buildings but that there were lots of barriers.”

There was concern about fire, rodents and insects, he notes.

“But if you keep the materials dry, it lasts for a very long time,” he says. “It’s like the three little pigs—building a house out of wood, straw or brick. These buildings are sturdy.”

And Niehaus, he says, was passionate and determined.

“With her, I really had no worries,” he says. “Because, if you think about it, the way in which we build is actually pretty primitive. It’s getting better. But the building trades evolve very, very slowly. It takes visionaries like Emily to push the envelope to find other ways to build efficiently. Her homes are very affordable, net zero buildings.”

In 2015, Community Rebuilds expanded its model through a partnership with Hopi Tutskwa Permaculture, to support the Tribe in replicating the student education program on the Hopi Reservation and build homes for low- and very low-income families.

By the end of 2016, Niehaus and her crew had built homes in three rural communities on the Hopi reservation in Utah and in Colorado. In the latter, one of the homes makes her especially proud—a three-story duplex located at 9,500 feet elevation in the exclusive Mt. Crested Butte neighborhood, one of the nation’s most expensive places to live.

“You can find homes for sale there at $800,000,” she notes. “So I can appreciate what it took to get our project built there.”

Her pride, however, is still mixed with awe.

“I didn’t know back in 2010 if all of this was just a pilot or if it could be something more,” Niehaus says. “The fact that we’ve built 22 homes since 2010 …. Looking back, I’m just so surprised. And the only reason we’ve been able to build this many homes here is because of the incredible partnership we have with the USDA and RCAC.”